When Matt Groening’s “The Simpsons” debuted during the Christmas season of 1989, it was an immediate sensation. Some fans might have known the Simpsons characters from their appearances on “The Tracey Ullman Show,” and readers of local indie newspapers likely knew of Groening’s “Life in Hell” comic strip, but for most audiences, “The Simpsons” was a bolt from the blue. It was an anti-sitcom, a surreal show with weirdly designed characters (yellow skin?) that satirized and deconstructed the middle-class wholesomeness of mainstream 1980s television. It was an antidote to the ultra-conservative “family values” crowd that was so noisy during the Reagan administration. And audiences were ready for it.

“The Simpsons” started big and only got bigger. The year 1990 was big for pop culture, as “The Simpsons” — along with shows like “Seinfeld” and “Married… with Children” — undid old tropes and invented new ones. One might even be so bold as to claim that Groening’s show invented the singular prevailing attitude of the following decade: disaffected, whimsical, educated sarcasm.

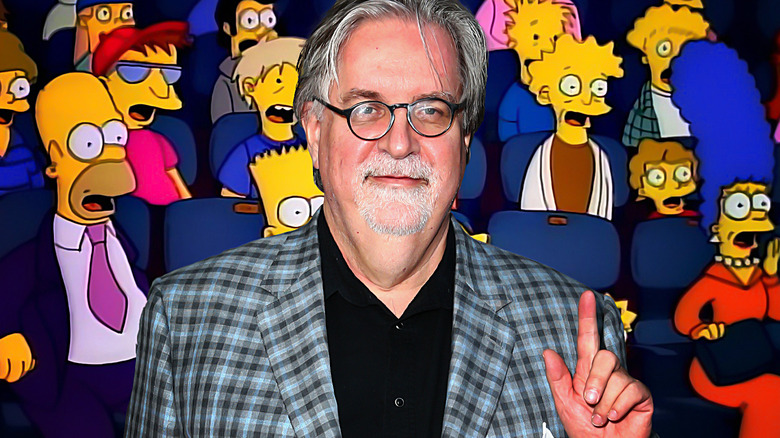

Groening knew “The Simpsons” was going to be a cultural juggernaut pretty early on in the show’s run. He was likely glad that the series was a hit, but he didn’t really acknowledge that “The Simpsons” was a massive commercial presence until he saw one episode in particular. In a 2018 interview with USA Today, Groening said that the second-season episode, “Bart the Daredevil” (December 7, 1990), really unlocked the series for him. That one, he knew, made the show special.

‘Bart the Daredevil’ marked a change in The Simpsons

In “Bart the Daredevil,” the Simpsons attend a monster truck rally where they witness a stuntman named Captain Lance Murdock (Dan Castellaneta) botch a motorcycle jump and get horribly injured. The spectacle inspires Bart to start jumping over things on his skateboard, eventually declaring that he, too, wanted to be a daredevil. Marge (Julie Kavner) and Homer (Castellaneta) try to talk Bart out of doing dangerous things, but his resolve only becomes stronger. He eventually declares that he will jump Springfield Gorge on his skateboard.

Homer, to teach Bart a lesson, takes the skateboard and does the jump himself. As might be predicted, Homer doesn’t make it. He plummets to the bottom of the gorge, landing with broken bones and blood. The skateboard even lands on his head for additional injury. When Homer is airlifted out by a medical helicopter, they thwack his head several times on the gorge wall. Homer is loaded into an ambulance, which immediately crashes into a tree. His gurney rolls out of the back of the ambulance and plummets back down to the bottom of the gorge.

In USA Today, Groening was asked when he knew that “The Simpsons” had become a classic, and he was quick to mention “Bart the Daredevil.” Notably, Groening said:

“The episode where Homer skateboards over Springfield Gorge … almost. It made me realize we’ve really got something. It’s like classic Warner Bros. [cartoons], but we can do our own variation. Homer goes over the cliff. He doesn’t make it. He hits the wall all the way down. The skateboard lands on his head. He gets raised up on a gurney and bangs his head all the way up. He gets put in an ambulance that hits a tree. The gurney rolls out and he goes over the cliff again. It’s that extra plummet. That’s ‘The Simpsons’ at its best.”

Indeed, Homer’s repeated injuries revealed a timeless comedic quality. “The Simpsons” officially had the staying power of the Looney Tunes. It was permanent now.

‘The Simpsons’ mixes the high and the low

Groening, along with the world’s many “Simpsons” fans, understood that the series was a glorious mix of the high and the low. “The Simpsons” was clearly written by well-educated writers who were permitted to drop in math jokes, literary references, and civics trivia at their whim. All the while, the show features slapstick violence, belches, and cheap gags about casual domestic abuse. As an old friend of mine once put it: If you’re uneducated, you will laugh. If you are educated, you’ll roar.

Groening always liked that about “The Simpsons.” It was ultimately a brainy show, but it certainly wasn’t above a bleak, Coyote-like slapstick sequence wherein Homer Simpson is repeatedly injured in multiple falls. As Groening put it:

“The show is a forum for comedy ideas. There are very sophisticated references to great literature and cinema, as well as the most basic slapstick cartoon gag.”

Homer Simpson is a dumb boob, but “The Simpsons” also has had cameo appearances from the likes of John Updike, Amy Tan, Stephen Hawking, and Thomas Pynchon. And that’s just a few of the hundreds of celebrity cameos besides. They know how to poke fun at famous people and their place in the pop pantheon. For many years, “The Simpsons” has been a consistent cultural hub and primordial comedy soup from which American culture grows. It may be less of a force in 2024 as it was in 1990, but it’s still around to remind us of where we all came from.