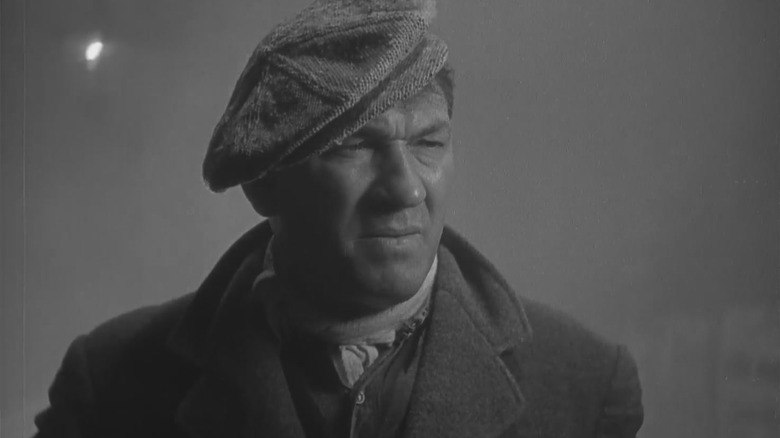

Plenty of Hollywood creatives spend their whole careers trying to win an Oscar, but some of them don’t seem to care. Or if they do care, some of them have other concerns that take top priority. Such was the case with Dudley Nichols, a screenwriter whose career spanned from “Men Without Women” in 1930 to “Heller in Pink Tights” in 1960. In 1936 he won an Oscar for “The Informer,” an acclaimed film about an Irish informant riddled with guilt after betraying his friend in the IRA.

Although “The Informer” is not too well-known these days, in the decades after its release it was commonly cited as one of the best movies in American cinema. In 2024, however, the movie is best known for what happened when its screenwriter won an Academy Award. Nichols, who was a co-founder of the Screen Writers’ Guild, wasn’t happy with the Academy’s refusal to acknowledge the SWG or to support its fight for better pay and proper credit for their work. He boycotted the ceremony, and when the Academy tried to mail him his award, he sent it back and wrote an open letter in response:

“As one of the founders of the Screen Writers’ Guild, which was conceived in revolt against the Academy, and born out of disappointment with the way it functioned against the employed talent in any emergency, I deeply regret I am unable to accept this award,” Nichols wrote. “To accept it would be to turn my back on nearly 1,000 members of the Screen Writers’ Guild.”

Dudley Nichols’ 1936 protests were a success

The head of the academy at the time, Frank Capra, said in response to Nichols’ protest, “Membership in the academy has no connection with an award and never has. Dudley Nichols’ award will stand, even if he does not accept the statue which is merely the symbol of the award.”

Nichols did eventually accept his Oscar in 1938, but only because he achieved most of his goals for the SGA. As the Santa Ana Register reported the same year, “The National Labor Relations Board today certified the Screen Writers Guild Inc., as exclusive bargaining agents for approximately 325 writers employed by 13 Hollywood motion picture studios.”

It’s not all that clear how much of an effect Nichols’ Oscars boycott had on this result; looking through newspaper archives, it doesn’t seem like any journalists made the connection between Nichols’ 1936 boycott and the SGA’s 1938 breakthroughs. Before and after the SWG was certified, it was common for newspapers to mention Nichols’ Oscar win for “The Informer” without mentioning his boycott of the award or his reasons for it. Even for Nichols’ obituary in 1960, newspapers would often neglect to mention this detail, even though Nichols’ refusal of the award was undoubtedly one of his cooler moments.

Still, Nichols’ boycott of the 8th Academy Awards was just one of many moves he made in the fight for better conditions for screenwriters in Hollywood. In the same year he was boycotting the Oscars, the Screen Writers’ Guild would rapidly grow and gain influence, even though so many newspapers were seemingly in the tank for the producers the guild was fighting against. “The Screen Writers’ Guild is a device of Communist radicals,” wrote the Washington Herald in April of that year, “who apparently do not mind cutting their own throats if they can only manage at the same time to cut the throats of the producers and the workers generally.” For those who haven’t forgotten the latest 2023 WGA strike and the discourse surrounding it, this argument against the writers’ union sounds awfully familiar.

Nichols and the other Guild members kept up the fight regardless, and most of the rights they fought for were achieved, including “shorter optional contracts, power to determine credits, [and] a deposit on speculative work.” This made life easier not just for themselves but for the generations of screenwriters who would follow them. The success of later writers’ strikes owes a lot to the struggles of Nichols’ early work.

Dudley Nichols fought for Hollywood unions during a very chaotic time

Why were newspapers so hesitant to mention Nichols’ Oscars boycott? Perhaps it was because a lot of them at the time were too busy fearmongering about potential Communists within the union Nichols helped found. “Unquestionably there are undercover Communists in the writing business here who would like to impose the closed shop and, by adroit but recognizable methods, exclude from the screen ideas contrary to their own,” wrote one columnist in 1938, adding, “Radicals are rather free with their use of such words as ‘fink,’ ‘scab,’ and ‘house union’ toward those who jerk away from their attempts to coerce and terrorize, but any mention of communism in connection with their activities is denounced as red-baiting. But red-baiting should be recognized as a legitimate defense action. They like to dish it, and they will have to take it.”

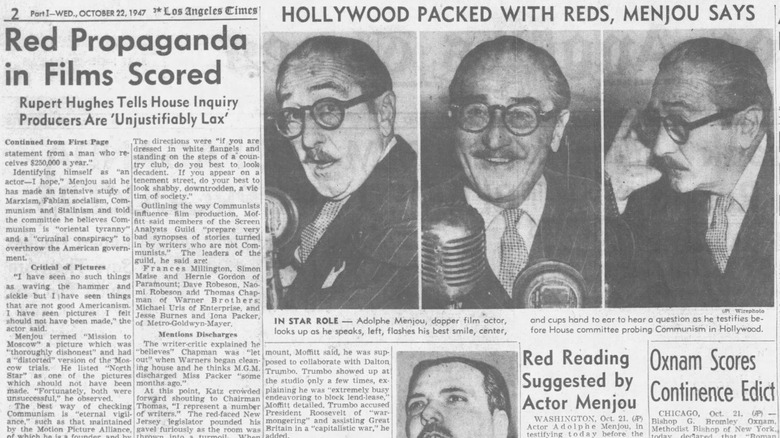

This columnist was Westbrook Pegler, a guy who also really hated the New Deal, disapproved of labor unions in general, and opposed anti-lynching legislation for good measure. Although not particularly well respected now, Pegler was at the height of his influence in the 1940s, helping pave the way for the Second Red Scare that severely impacted the SGA. Throughout the 1940s the House Un-American Activities Committee investigated countless creatives in Hollywood for alleged Communist affiliations. Although the idea of Communist infiltration in Hollywood would later be seen as more of a moral panic than a genuine problem, the damage to a lot of screenwriters’ careers (many of whom were blacklisted from Hollywood altogether) couldn’t be undone.

Not even McCarthyism could bring Dudley Nichols down

Dudley Nichols survived the Second Red Scare mostly unscathed, although as a prominent figure in the SWG, his character was still maligned throughout this period. Writer Rupert Hughes testified that Nichols, who he described as “certainly very leftist, although I don’t know whether he is a Communist,” had “demanded” the request of Hughes’ resignation in 1932 due to Hughes’ anti-communist beliefs.

The accusation was never proven; looking through the records, it seems more likely that Hughes’ and Nichols’ falling out in the early ’30s was the result of their different views on how the SWG should operate. “Every time we have an olive branch these men see the cloven hoof,” Nichols had complained in 1938. “They imagine any writer bold enough to stand up for his reasonable rights must be a radical.”

As the Second Red Scare slowly died down and the writers’ union remained intact, Nichols kept on writing screenplays and continued being a venerated, award-winning figure in the industry. As the Tulsa World newspaper reported in February 1954, “The Screen Writers’ Guild Thursday night gave its Laurel Achievement award, emblematic of the biggest contribution through the years to his craft and the guild, to Dudley Nichols. Nichols has written such distinguished movies as ‘Prince Valiant,’ ‘The Big Sky,’ ‘The Bells of St. Mary’s,’ ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls,’ ‘Stagecoach’ and ‘The Informer.’ The award was made at the guild’s annual dinner and was the decision of its 21 board members.”