[ad_1]

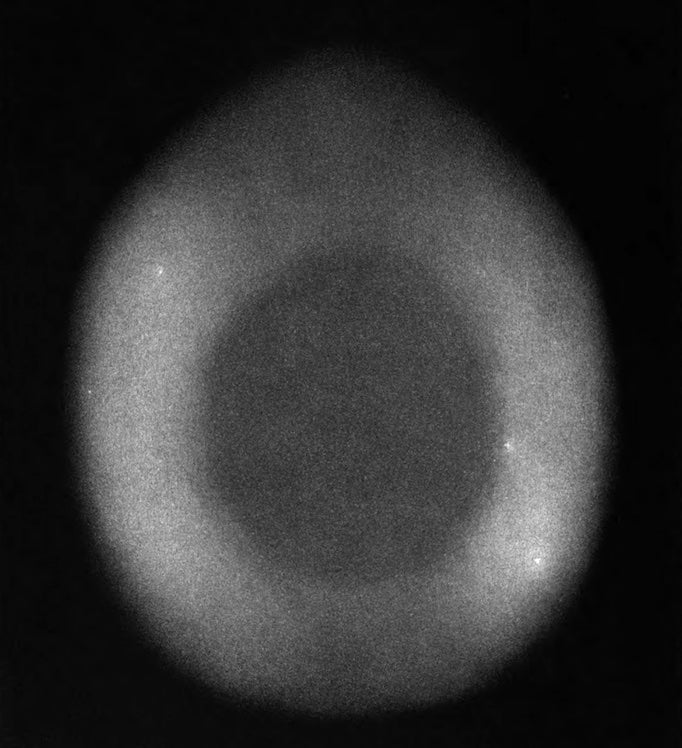

This 1874 lithograph was created by Étienne Léopold Trouvelot with the 15-inch refractor at the Harvard College Observatory, for the purpose of measuring the nebula’s extent. A glass plate with dark black lines was placed on the focus of the telescope for marking placement. No wonder it shows no central star. Credit: Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College (Vol. 8)/NASA ADS

The Ring Nebula (M57) in Lyra is one of the most adored planetary nebulae in the night sky. Yet its bright annulus, which is most observers’ target, can steal attention away from what lies inside it.

This includes its central star, which lies at the limit of vision and is a rewarding challenge to spot. So let’s take a plunge into this nebulous doughnut hole, the twilight zone of deep-sky observing. As Rod Serling intoned, inside the Ring lies “a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of the imagination.”

Your next stop: the Ring Nebula

As with many discoveries, the Ring’s subtle features were detected in stages over time. When Charles Messier discovered the object Jan. 31, 1779, he observed it as a “small patch of light.” A few days later, his contemporary Antoine Darquier detected hints of an annulus: Its center, he said, appeared “a bit less pale than the remaining part of its surface.” In 1785, William Herschel discerned that region as a “regular, concentric, dark spot in the middle.” But it wasn’t until decades later that Herschel’s son John noted the empty space was filled “with a feeble but very evident nebulous light … like a gauze stretched over a hoop.”

When Messier discovered the object, it was thought that all nebulae might be unresolved star clusters. Thus, early attention was focused on the Ring’s annulus to see if it could be resolved into stars, not on the core.

But then a most mysterious discovery occurred in that hazy twilight zone. Around 1795, German astronomer Friedrich von Hahn began observing the Ring. Five years later, he announced he had discovered a central star. Strangely, some observers using large apertures failed to see it, while those using smaller telescopes had success. What’s even more surprising is that Hahn made his visual discovery using a 12-inch Herschelian reflector with a speculum-metal mirror that was likely only about 65 percent reflective (compared to today’s silver coatings of some 98 percent).

Adding to the mystery, during the five-year gap between starting his observations of the Ring and publishing them, Hahn himself lost sight of the central star — though he gives us a clue as to why: “A few years ago the interior of the ring was so clear that I could distinguish in its centre a telescopic star with my [12-inch] reflector. Now this telescope shows only faint fine clouds and the small star is no longer visible.”

It’s unfortunate that, to my knowledge, Hahn documented no magnifications for these observations. If he had, he may have answered his own question. In short, if you can see the feeble light within the annulus, your chances of sighting the central star are low. And this correlation is directly related to magnification. High magnification lowers the contrast between the Ring’s hole and the background sky, making the central star more accessible. You’ll want a power of around 600x, and a telescope with excellent optics that can handle it.

One more tip: Your mental focus needs to be solely on the central star and not the Ring. The smallest telescope through which I have seen the central star was the 9-inch f/12 Alvan Clark refractor at the Harvard College Observatory, using 650x with my favorite eyepiece (a 1/3-inch Fecker) that gave a field of view of only 10′.

The same rule applies to the other extreme of aperture size. Using the 1-meter f/17 Cassegrain reflector at the Pic du Midi Observatory in France, astronomical historian William Sheehan and I viewed the Ring Nebula at 1,200x. The view was solely of the Ring’s twilight zone; the ring itself was outside our tiny field of view. We saw only two objects: the magnitude 14.5 central star (our estimate; other reports place it at 15.8) and its similarly bright neighbor to the northwest. In comparison, the view through the 1-meter f/17 Cassegrain reflector at Lick Observatory in California was completely different because we were limited to a moderately low power. The Ring’s empty inner region was filled with bright striated cirruslike clouds. After some time, I could, on occasion, glimpse the central star, but it was quite a struggle.

The bottom line is: If you want to see the central star of the Ring Nebula, increase the power to the limit and use eyepieces with small fields of view. Prepare to dedicate a night’s session to the challenge. Be patient. Breathe. And as always, tell me what you see or don’t see at sjomeara31@gmail.com.

[ad_2]